It’s hard to write about Ben West without “feeling it deep in the heart” as Weston Nordgren put it so well on Twitter.

I’ve been fascinated by Ben ever since I discovered the lengths he went to to liberate diabetes data over a five year period, starting in 2009.

Ben’s work, Decocare, formed the central part of the OpenAPS toolkit he developed in collaboration with Dana Lewis and Scott Leibrand.

Nate Racklyeft, developer of DIY Loop, described it as Ben’s magnum opus.

It remains the foundation of all the systems in use today, either literally or spiritually. (Nate, Facebook, 2017)

For more than ten years now, Ben has been involved in changing the status quo in diabetes through his work with the Nightscout Foundation, Tidepool and Dexcom and by making submissions to regulators.

When I discovered his writing, presentations and interviews, at the end of 2017, I also became intrigued by his integrity, his quiet activism, and the way he spoke about diabetes in a heartfelt, nuanced, and deliberate way. (See links at end of post.)

It was a breath of fresh air for me after 38 years of living with type 1 diabetes.

When I spoke with people who know Ben at D-Data last year, and recently on Twitter, the first thing that became obvious was the strength of feeling people have for him. Two people said outright, “I miss Ben.” One of them had moved to a different country. The other was in a different city to Ben, but had known him well during his decoding and Nightscout days in San Francisco.

I wondered, “What sort of person is it that is so deeply missed?” When I met Ben in San Diego a week later, things fell into place.

Firstly, Ben tells the truth. Although he sometimes keeps you on your toes by putting a cryptic (not to him) or evocative spin on things. A spade is definitely a spade with Ben, unless it’s a squirrel-shaped thing. Ben likes to play with words. But if you ask him, and he answers, you’ll get right to the core of the truth. That means it isn’t always going to be comfortable for everyone in the room.

Like others in the We Are Not Waiting movement, Ben has a strong drive to move things forward to a better place while many of us are still catching up with the past.

The thing with Ben is, his IQ is off the scale. We wanted to find an investor to set him up for six months and just leave him to it. (Weston Nordgren)

There are not many kinder or more selfless than Ben. (Melinda Wedding)

When my plane touched down in San Diego last November, to meet with Ben, I found he had sent me a photo of his car, told me exactly where the airport exit would spit me out using a clear symbol that I’d recognise, and got out of his car to greet me. Clear, confidence-building instructions. And a warm welcome. This is exactly the type of person I want designing my diabetes apps. In fact, these are exactly the things I want in my app.

And the good news is, Ben has been designing them.

When I met with Ben last year, he had been working for Dexcom for three and a half years, and had a sizeable list of features in mind that would make life easier for people with diabetes.

He also talked about his research into building trust through automation. I was intrigued, as someone who’s done research into user trust in technology myself, and I was grateful that someone was thinking about diabetes design through this lens.

As Katie DiSimone of Tidepool puts it: “The contributions Ben continues to make regarding quality of life considerations in device design, and access, are equally as impressive to me as his decoding and open source contributions. He’s a real asset to us all.”

Ben’s impact went even further for me.

His words and ideas, from the moment I encountered them, kicked me out of a kind of psycho-cultural ‘diabetic coma’. They jolted me into a new way of seeing diabetes and the culture I’d been immersed in since childhood.

The whole DIY movement turned the diabetes narrative around.

Here is how I tried to explain it in my first draft of this blog post:

I didn’t recognise the state I was in, because from age 12 it had become part of my identity. My schemas (the way I understood the world) were still being set up when I was diagnosed with diabetes.

The myths of insulin as cure, and diabetes as manageable, were pervasive.

But diabetes wasn’t manageable for me.

My attempts were misguided, the tools too blunt. And I wasn’t alone. But I didn’t realise it.

Like many others of my generation, I blamed myself and tried not to think about the future. Because of diabetes. And because of the diabetes myths.

The lightning struck for me in November 2017 when I discovered that people who had diabetes themselves, or had children with diabetes, had taken matters into their own hands and created closed loop systems. It was a serious overnight antidote. And I started my mission, with a kind of obsessive zeal, to try to find out as much as I could about the pioneers of the We Are Not Waiting movement.

War, truth and compassion

I loved Lane Desborough’s outing of diabetes itself as the common enemy. It was a war and it was a war we were going to win.

And John Costik, with his beautiful love and compassion for his son, Evan. When Evan asked him, “Make it better?” John responded, “If I can, I will.”

John’s cliff edge metaphor for diabetes was just one example of how the pioneers of this movement were the ones (for me) to finally call out diabetes for what it really was. His comments about insulin being a potentially lethal drug we are sent home with, and told, “give this to your son, maybe he needs this much. We don’t really know what the dose is. We’ll have to figure it out,” and “they don’t teach you how to integrate it back into your life. They don’t teach you how to be happy with it,” were spot on.

These were crumbs of compassion that many of us were not able to feel for ourselves, as children and teenagers (any age actually) due to the prevailing ‘pull yourself up by the bootstraps’ ‘if you just try hard enough’ attitudes towards type 1 diabetes at the time. Truth and compassion were being expressed by parents of children with diabetes. I absorbed every morsel I could find.

And the best thing was, it didn’t stop there. These same people were the ones actually doing something about it. Inventing tools that would change diabetes forever.

Poetry and resistance

Ben’s ideas first caught me by surprise when I read the Diabetes Hacking 101 article about him and watched his Stanford Medicine X 2016 presentation.

There he was, this young guy, with his thoughtful, ironic smile. Going back to first principles. Reframing the problem of diabetes and choosing his words carefully. There was no way he was going to let any of it stick to him. And this was incredibly powerful to see.

The words Ben used caused my brain to do a kind of quarter turn. It was like a deep mind reset button had been pressed and there was no turning back.

He referred to his insulin pump as the thorn in his side. He was toying with the audience and being serious at the same time. Weaving metaphor together with logic. Tentacles of layered meaning invoking the senses. I really enjoyed this use of language in the diabetes context. It was refreshing. Made me smile.

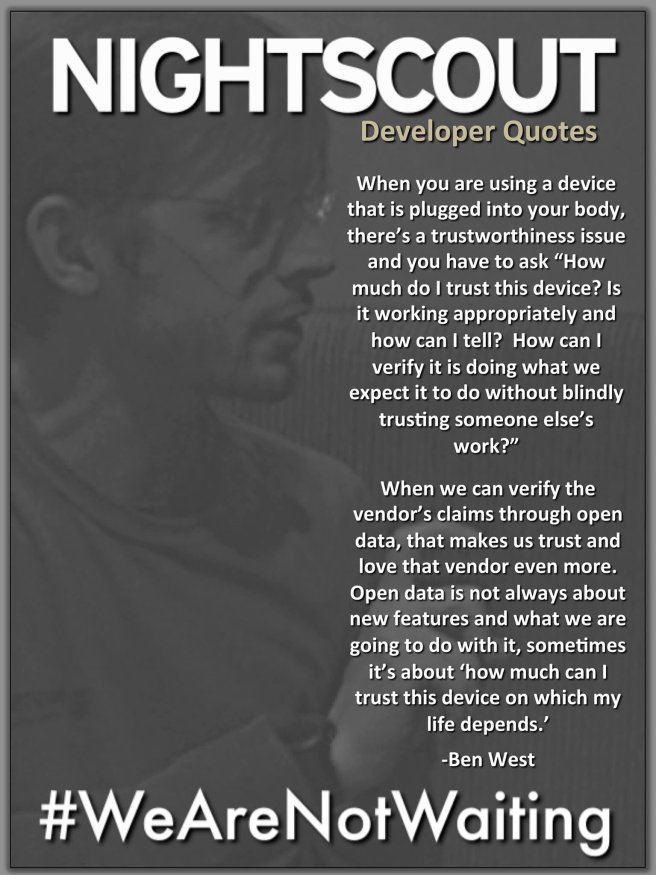

Ben spoke of the intimacy of the devices we have plugged into our bodies. Another quarter turn. We get so used to having these things on us and in us. By pointing out just how intimate our relationship with these devices was, and how our lives depended on them, he was strengthening the case for a patient’s right to access their own data, and to access their device protocols, in order to verify trustworthiness.

It was one thing for vendor reports to insist that the technology worked. It was another completely to be able to verify that it worked for your body.

Calling a spade a spade, ethics

In the Diabetes Hacking 101 article, Ben was asked about risk.

“What’s interesting with the risk is that [traditionally] we’re given a bunch of insulin and we’re told to take it. We hold people responsible for getting it right. That’s not a humane thing, there’s no way you’re going to be able to balance insulin with all your needs.”

It’s hard to know where to even begin when talking about the impact these words had on me. It was like a dose of soul medicine. And they got me thinking about ethics and responsibility in the whole post-DCCT era of type 1 diabetes care.

A sense of entitlement, right to your own data

How was the insulin pump making its decisions? Were the proprietary, hard-coded device settings making the correct decisions for your body? Ben called for the application of science to find out. He made the link to precision medicine.

I guess for me – when I stumbled on Ben’s writing, interviews and presentations, at the end of 2017 – it was the first time I felt a sense of entitlement. Why had I been settling for less? Forget the blame issues. I deserved better therapy.

Risk

The way Ben differentiated between the risks of diabetes and the risks of diabetes therapy, was another important distinction, as was his use of the term insulin reaction rather than hypo.

Even pointing out the risk that lay with reading a BG number from one computer (CGM) and typing it into the other computer (pump) was refreshing to hear. The practice was not only burdensome, but error-prone.

High fidelity therapy leads to humane care

Ben uses the term high fidelity therapy to describe therapy where effort is rewarded with results. This is a psychologically important feedback loop, important for mental health.

And to a large extent, for many people, it’s been missing in diabetes.

I was interested to see Eric Renard describe the task of keeping blood sugar levels in the safe, recommended range as “Mission:Impossible” in his recent article for the Journal of Diabetes, Science and Technology.

His opening sentence was clear: “Type 1 diabetes is among the toughest health conditions to manage both by the affected patients and by the healthcare professionals who assist them.”

Now that we have high fidelity therapy, tools for remote monitoring and artificial pancreas systems, it is easier for us, collectively, to see and acknowledge how difficult the task of type 1 diabetes has always been, for all involved.

With tools to both understand the factors involved in a detailed way, and address them, a new, more honest, collaborative and useful discourse is emerging.

Time well spent – Time on task

Quality of attention, embracing life, being in the moment. The gift of giving someone or something in your life your undivided attention.

One of the answers to “why do people miss Ben?” is surely the fact that when you are with him, he gives you his full attention.

Ben was most generous with his time. I deeply appreciate all his initiative and leadership. (Martin Haeberli)

Ben uses the term Time On Task to describe the need to develop technology that allows us to focus on life and and not have diabetes break our flow. Technology that minimises the amount of time we are “pulled into screens” to manage our diabetes.

As someone who’s worked in usability consulting and education, Ben’s ideas about time on task really meshed with my own.

I’ve noticed differences between various diabetes systems in terms of how well they facilitate this, and have loved customising my own DIY systems to allow me to do things quickly on the fly.

I’ve been frustrated over recent years when new versions of insulin pumps emerged that seemed to decrease in usability with each iteration, presenting the user with an increasing number of steps to get a simple task done. I’m hopeful that this will change as human factors specialists, and people with diabetes themselves, are employed in industry.

Usable, intuitive design in medical devices is a crucial aspect of creating high fidelity, humane care.

I’m pretty sure I heard Ben suggest, at last year’s American Diabetes Association conference, that Time on Task could be used as an outcome measure for diabetes in addition to Time In Range. I really love this idea. What a great thing to focus on in a medical consultation. How’s your time on task going? How’s your ability to focus on life without being interrupted by diabetes going?

All, once again, part of Ben’s humane care principal for those developing diabetes technology to keep in mind.

Playing with diabetes

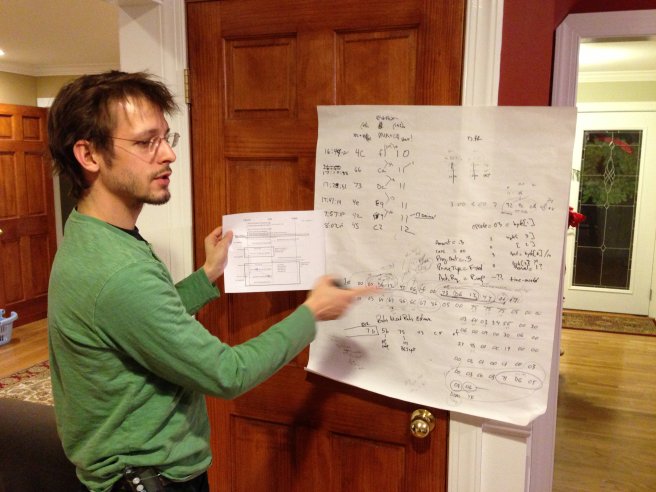

Like many programmers I’ve met, Ben is super creative.

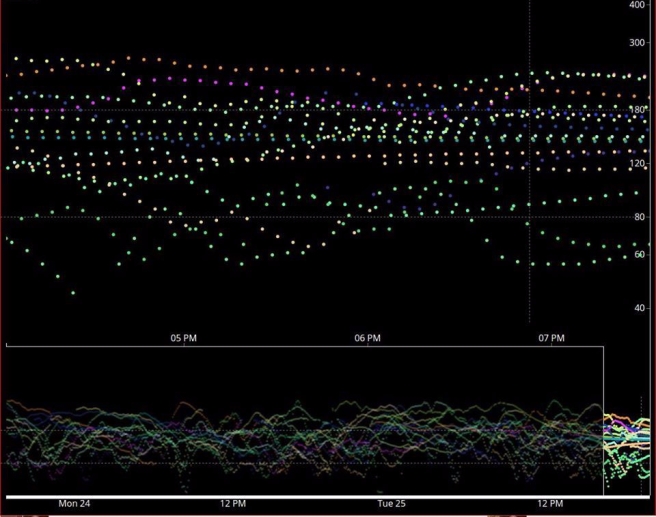

He’s done some fun experiments with sonification of blood sugar levels.

And if you want to get a feel for the magnitude of his contributions to diabetes, check out this animation he created which includes every commit he made to Nightscout, Decocare and OpenAPS.

Ben studied music and computer science at university, and initially planned to major in music and embark on a career as a performer. When he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes he changed his major to computer science, figuring he’d need a stable job in order to be guaranteed medical insurance in the US.

Ben sings and plays at least two instruments, piano and ukulele.

Building community

I also love the way Ben plays with technology to bring people together as a community. He has some really interesting ideas on ways to make the task of diabetes more of a shared, supportive experience.

In November 2014 he staged an ‘empathy building experiment’ where people added their Nightscout URLs into an aggregator to produce Halloween lights.

Who is Ben?

One of the things that really intrigued me about Ben was, where did he get his persistence and drive from, to continue with that initial reverse-engineering work, in the midst of so much uncertainty, for so many years?

Some clues lie in his background.

Raised in New Jersey, Ben is the son of Earle West, former Technology Operations Director with AT & T Bell Labs and holder of 13 US patents. His family held their own Summer hackathons and gave Ben a solid grounding in critical thinking and the classics. In elementary school, on Careers Day, where people demonstrate what they do, Earle built a working telephone network from the bare electronics in a live demo in Ben’s class.

When I asked Ben where he got his drive from he said:

I’m a white male raised by evangelical parents. I benefit from all of white male privilege in America. So I can use that in ways that will benefit people in general.

And the interesting and unfortunate fit is that needing insulin this way is destabilizing for a lot of people in ways that can be fixed – in ways I have technical expertise in solving.

Ben mentioned the parable of the two sons.

“But what do you think?

A man had two sons, and he came to the first, and said, ‘Son, go to work in my vineyard today.’ He answered, ‘I will not,’ but afterward he repented, and went. He came to the second, and said likewise. He answered, ‘I go, sir.’ but went not. Which of the twain did the will of his father?”

They said to him, “The first.” (Matthew 21:28–32)

A sense of purpose, mission

Ben encouraged people to share their code as open source. He asked people “what is your role going to be?” and helped establish the pay it forward ethos of the We Are Not Waiting movement.

Many people have found a sense of purpose in the movement, as well as a source of support, inspiration, new learning and community. There is a strong sense of loyalty.

Open science → innovation → high fidelity humane solutions

In Derek Russell’s interview with Ben for the Data Binge podcast, September 2019, Ben emphasised:

The important thing is not limit what could come in the future. It’s very difficult to know who is going to come up with the next great idea to enhance your own product.

There’s a lot of temptation in industry to say, well we shouldn’t leave any money on the table for someone else to collect. There’s an unfortunate harm that comes to society as a whole when we make decisions in such a way that it limits who has the ability to do that innovative work.

That’s one of the lessons we’ve learned from the DIY community. Given the chance, patients can help industry move towards greater innovation for the benefit of everyone involved.

When you have an ecosystem that’s accessible – an ecosystem that democratises the effort, and these humane concepts – this concept of high fidelity – the more effort that you put into the system, the results should be better for you.

If that becomes a requirement of every piece of technology you are working on, then the results are fundamentally going to be more humane for people.

Seeing new versions of artificial pancreas systems emerging from committed DIY developers every few months now, with increasingly advanced features, and a high degree of personalisation and customisation possible, it seems this vision is being realised in the open source community.

The energy is incredible. We all just feed off each other (Tim Gunn, AndroidAPS developer)

And who knows what the future holds? This process is also pushing industry and regulators to develop faster ways to bring more adaptive, usable systems to market.

In 2020, with the emergence of citizen science in the diabetes space, it feels like we are on the verge of gaining valuable new insights from collective n=1 experiments, and patient-led initiatives like the OPEN research consortium. These outputs are highly relevant to people with diabetes, because they are patient-led.

Pressure

I like to keep in mind the fact that Ben, and the other early innovators in the We Are Not Waiting movement, were involved at a time when there was a great deal more uncertainty and trepidation about legal implications.

“I was keeping my head under the radar,” Ben said on Twitter.

There was a lot of excitement and community good will, but there was also a lot of pressure. A lot of responsibility.

My whole Nightscout/looping journey is thanks to Ben. (Kate Farnsworth, creator & moderator of Looped group on Facebook, which now has over 21 000 members)

Along with others, Ben was involved in early meetings with the FDA and sought legal counsel along with Hugo Campos, Karen Sandler and Jay Radcliffe, which resulted in patient access to data being legally endorsed through a DMCA exemption for medical device research.

He worked unpaid on the open source diabetes project for some time without health insurance. I can only imagine, that for someone with type 1 diabetes in the US, this must have been anxiety-inducing at times.

As the number of DIYAPS users grew, the demand for help online grew too. People chipped in from all parts of the globe to help answer questions. Exuberance and gratitude levels were high, but still, volunteers were stepping in to fill a need unmet by the diabetes establishment, and the need was significant.

I can only imagine that the pressure on some of the key people involved in the movement must have felt, and must still feel, very intense at times.

The questions, opinions, and imperatives rolled in from users and non-users alike in the chat room. It didn’t take long before I felt overwhelmed.

I hadn’t realized that passion projects could outlive their passion, but it happens every day in open-source projects. Loop was going to be an endless “loop” of development unless I took steps to slow down. (Nate Racklyeft, who now works at Apple.)

Ben described the pressure too, saying by the time he moved from San Francisco to San Diego to begin work with Dexcom in 2016, he’d been “living and breathing” open source diabetes 24/7 for years.

“There was a lot of pressure” (Ben)

Ben said he intentionally didn’t get internet connected at his new home for some time.

I’m guessing he needed a break. Some recovery time.

We visited a beach where Ben used to spend as much time as possible, gazing out over the ocean, after his move to San Diego. It was a beautiful spot.

Power and control

As with all areas of health and society, power imbalances and issues around control have influenced the evolution of care and innovation in diabetes.

In Derek Russell’s Data Binge podcast Ben says:

Patients across the board have this power asymmetry from the people providing them care. Whether from health care professionals or vendors.

Ten years earlier, he’d identified the issue in Github:

As Thucydides said

Right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. (Github – Bewest Insulaudit)

Getting access to the data in a usable format, and having access to the insulin pump protocol, was an absolutely critical aspect of restoring power and agency to people living with diabetes.

With so much already achieved, Ben continues to advocate for open source practices to become a mainstream part of medical device development.

As recently as September 2019, Ben testified at the FDA’s Patient Engagement Advisory Committee meeting about the need for device manufacturers to invite patients to examine medical software prior to devices reaching the market, in order to help iron out bugs and safety issues.

As Ben notes, in the Data Binge podcast, there is still work to do:

Across the board in healthcare, the fidelity of the experience that we get is not where it should be.

Ben mentions some of the initiatives that are emerging to help create better health outcomes and increase patient satisfaction, leveraging the power of data and technology to drive better incentives and a better patient experience.

Ten years on, with three DIY closed loop solutions available, remote monitoring through Nightscout, diabetes management solutions through the non-profit, Tidepool, and user-centric industry solutions finally coming to market, the power balance has shifted significantly.

As one Australian DIY looper said:

“In 34 years of living with type 1, it’s the very first time that I’ve felt absolutely in control of what’s happening.” (Schipp et al, 2020)

As Ben hangs in there, like the rest of us, through this crazy 2020-21 COVID era, I hope he can pause and feel good about the incredible difference his efforts have made to so many peoples’ lives, including my own. I hope he can feel it deep inside his heart.

To all the pioneers of this movement, to everyone out there on Gitter, Zulip, Facebook, Slack channels, Twitter, everywhere. To everyone writing code, trouble shooting, advocating for access, holding build events, researching, developing user-centred solutions for non-profits and industry, fast tracking knowledge as citizen scientists, moving things forward…

THANK YOU

Let us all consider how we can unify our demands for trustworthy, high fidelity therapy that in adapting to our lifestyles allows us to return to the lives we want to pursue with the people and activities we love. Let us make the benefits we discover accessible to as many as possible. (Github Bewest/Insulaudit, 2018)

Update April 2021

In June 2020, Ben created a new business venture, Medical Data Networks, with his father Earle. The first stage is T1Pal, a Nightscout hosting service, which incorporates extra privacy and security features, and gives users a simple way to create and revoke ‘sharing links’ to their Nightscout sites. Ben has a vision to evolve this to underpin a new ecosystem of high fidelity therapy for people using insulin, which he likes to refer to as Diabetes 2.0. Watch this space!

References

Ben’s writing, ideas, code on Github

Stanford Medicine X 2016, Ben’s presentation

Dana Lewis, Karen Sandler, Cédric Hutchings, Ben West: panel discussion Stanford Medicine X 2016

Weston Nordgren’s interview with Ben, 2016

Diabetes Hacking 101 WNYC Studios, interview with Ben, 2016

Data Binge podcast with Derek Russell, Sept 2019

History of Loop and Loopkit by Nate Racklyeft, 2016

History of DIYAPS by Dana Lewis, 2019

John Costik’s talk at MakeHealth Fest 2014

Sad State Of Diabetes Technology, Scott Hanselman’s pivotal 2012 blog post

Diabetes Mine story on Ben, 2013

Eric Renard’s article in the Journal of Diabetes, Science and Technology, 2020

State of Type 1 diabetes T1 Exchange article Management and Outcomes 2016-2018

One year of DIY looping after 38 years of type 1 diabetes (Journal article, Mary Anne Patton)

DIY Loopers take diabetes into their own hands (Science Show, Radio National, with Jim Matheson, Mary Anne Patton and Tien-Ming Hng.)

My DIY artificial pancreas and the rise of the We Are Not Waiting movement (Guest lecture, Mary Anne Patton)

Elinor Crawley’s speech to the National Paediatric Diabetes Audit, UK, 2020

iPhone Shortcuts for OpenAPS (Mary Anne Patton)

Six years in five minutes, visualisation of Ben’s commits to Nightscout, Decocare, OpenAPS

Ben’s sonification experiments, ‘listening to glucose’

Legal, DMCA ruling on patients accessing their data

DMCA exemption ruling, Harvard Law School, 2015

FDA Patient Engagement Advisory meeting, 2019

Experiences of user-led diabetes technologies among Australian adults with type 1 diabetes Jasmine Schipp, Jane Speight, Edith Holloway, Renza Scibilia, Henriette Langstrup, Timothy Skinner & Christel Hendrieckx. (poster, ATTD2020)

We Are Not Waiting Manifesto (Diabetes Mine, 2014)

And finally – Quantified Self Public Health meeting, May 2016 – In response to the suggestion that “in a few years we might just have a closed loop artificial pancreas system,” Dana Lewis announces that actually, eight people in the room have one right now, and Mark Wilson, Ben West, Jason Calabrese, Jim Matheson, Jason Curry, Mikel Curry, Erzsi Szilagyi and Scott Leibrand, file onto the stage.

Wow there is a lot of info here! I think it might take a couple of days to wade through but super interesting stuff.

LikeLike

Thanks Sam! It’s great to get your feedback. I just took a look at some of your blog posts too. Having a little one with diabetes must be so hard. And what you said about carbs is spot on.

LikeLike

That’s good to hear on my carbs post! Thanks. I did try to pitch it carefully so glad you thought it hit the right note!

LikeLike

I really appreciate your way of writing. I think you should write more on this topic .

https://www.comfortfinds.com/

LikeLike