Thank you to the organisers of the Advanced Technologies and Treatments in Diabetes conference for granting me a press pass to attend this year’s conference virtually.

As someone who’s worked in psychosocial health and human factors in technology research, as well as being a user of diabetes technology myself, I couldn’t help but be blown away by the vast amounts of user data the device companies have now amassed through automatic uploads, and the insights this has given them about how we actually use our devices. According to Professor May Ng, who presented findings from data gathered through Insulet Cloud, user consent is legally required for automatic uploads to the cloud in Europe, but consent is not required in the US.

This user device data is no doubt valuable to companies for understanding current device usage patterns and developing their next generation of tech. I wonder if it is also useful for us, as people living with diabetes, to help contextualise and normalise our experiences? We often hear about best practice guidelines, about what we should do, but how much do we know about what people actually do? I found myself thinking a lot about what lies beneath the surface of the findings presented at ATTD and it only gave me greater empathy for all of us navigating the gritty every day challenges of diabetes.

This blog post will touch on some of the human factors-related device data presented at ATTD2024, as well as some of the other “real world” research findings that I found interesting.

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), ‘fear of hypoglycaemia’ and agency

- In one of the first sessions of the conference, Alexandria Ratzki-Leewing cited research showing that the rate of severe hypoglycaemia for people with T2D on insulin was the same as for people with T1D

- She stated that 60% of people with T2D requiring insulin report reducing their insulin to avoid hypoglycaemia and

- many actually stop taking their basal insulin at some point during the first 12 months, especially if they have experienced hypoglycaemia. Boy did this help me to empathise with my T2D comrades.

- There was a big push for cgm to be made accessible to people living with T2D, especially those on insulin

- Some studies have found improvements when people withT2D use automated insulin delivery systems.

Bill Polonsky and others talked about the behavioural impacts when people with T2D had access to real time cgm

- Studies showed that people with T2D made changes (mostly to food choice) based on real time feedback via their cgm.

- Gained a sense of agency and a feeling of success

- This did not involve healthcare provider advice, but simply having access to real time cgm. Huge gains in agency when they could see that what they were doing was having an impact.

- Bill Polonsky suggested “Don’t give them psychotherapy, give them CGM”.

Type 2 diabetes, exercise and intermittent fasting

Although not related to device use per se, Mike Riddell reported on studies confirming that:

- Exercise for people newly diagnosed with T2D increased their beta cell function.

- Intermittent fasting can reduce A1c, body weight and insulin dose in people with T2D without the need for any other changes in diet (see references at end of blog post)

Optimal timing of meal boluses in T1D

This was one of my favourite presentations at ATTD 2024 and I was fascinated by the massive controversy at question time, with people asking the presenter, dietician Maya Laron Hirsh, for more details about the study and doubting whether it could be replicated.

Confession: I do not pre bolus, well, hardly ever, and despite being very happy with my overall TIR and A1c, I do tend to drift high after meals. (Not recommending this btw, it’s not optimal! I am just being up front about why I was drawn to this session. See end of this blog post for a great article on optimal meal dosing with AID systems by Dana Lewis, which for me is the gold standard.)

The presentation was prefaced by a slide indicating that 25-45% of people with T1D report “bolus mistiming” which Maya suggested was due to factors including fear of hypoglycaemia (the major reason), because it interferes with daily activities and forgetting to bolus. She stated that 1 in 4 meal boluses per day are “delayed” and that late bolusing while using automated insulin delivery systems can result in lows. She asked, do we need to change our advice around meal bolusing for people using automated insulin delivery systems? Do we need to update recommendations for people who bolus late to help them avoid hypoglycaemia?

Her team’s “proof of concept” study used Novorapid insulin and involved:

- 13 adults with T1D, aged 20-70, who’d used the Medtronic 780G automated insulin delivery system for over 6 months

- Participants were given one observational meal and, if needed, were supported by the medical team to change settings to meet their desired glycemic targets

- Participants were given a sandwich (2 slices wholemeal bread with cheese) and an energy bar, for breakfast, with 50g carbs, 50g protein, low in fat (500kCal in total, which is considered a ‘medium sized meal’)

- Meal bolus was given at four different points and each of the meal timing scenarios was repeated (8 meals in all)

- 10 minutes prior to meal

- With the meal

- 30 minutes after the meal (with a reduction of 50% of the carbohydrate actually eaten to see if this would minimise the risk of post-meal hypoglycaemia)

- 60 minutes after the meal (with a reduction of 50% of the carbohydrate actually eaten to see if this would minimise the risk of post-meal hypoglycaemia)

Results showed that for this particular meal type, the highest time in range (3.9-10mmol/L) was obtained by bolusing at the time of the meal, not before it.

She concluded that, for this study, there was no advantage to bolusing before a meal and that for people bolusing half an hour or an hour after the meal, a 50% reduction in the amount of carbohydrate entered for the late bolus prevented hypoglycaemia. People asked questions after the session at ATTD and on Twitter about factors which are known to affect meal bolus outcomes such as the nutritional composition and glycemic index of the meal, time of day of the meal, type of insulin used etc.

She indicated that for people who “couldn’t carb count well”, a fixed partial dose eg for pizza (with an automated insulin delivery system to manage post meal dosing) might be more helpful than having them trying to estimate fat and carb content, rate of carb absorption etc. She also suggested simplified bolusing might be helpful for people experiencing diabetes distress and burnout and stressed that people could then focus on the other things that could keep them healthy such as replacing infusion sets on time, exercising and eating healthy foods.

My own experience using OpenAPS/AndroidAPS, Loop and Tandem’s Control IQ has shown me that each system handles meals and meal bolusing differently, from both a usability and algorithm perspective, and I need to adjust my bolus behaviour (and sometimes system settings) to suit each algorithm. As someone who is hypoglycaemia-averse, I am watching the unannounced meal research in the open source community and the commercial device world with great interest to see if a system that removes the ‘onus to bolus’ can be developed that doesn’t incur added hypoglycaemia.

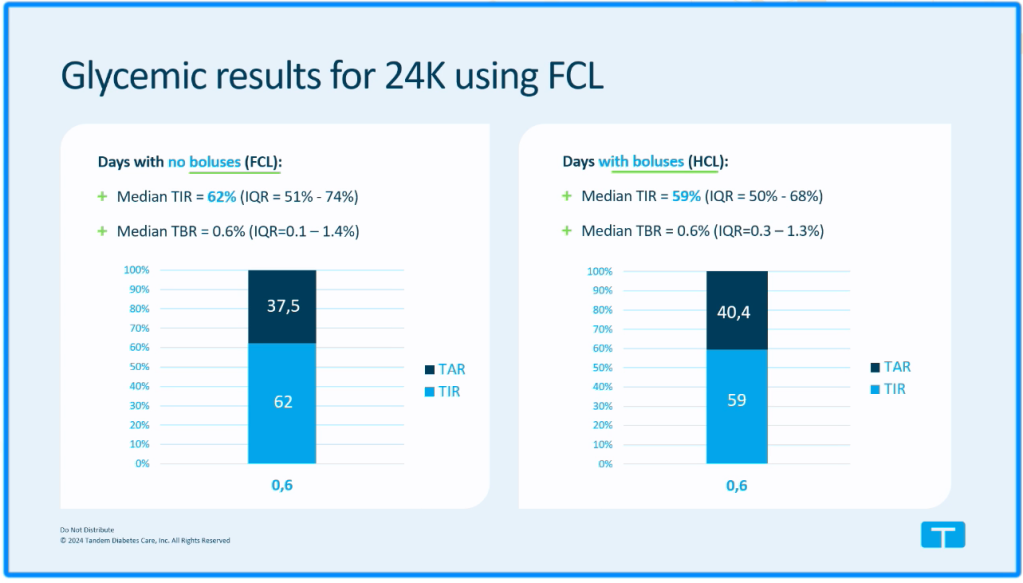

No bolus for over one week, 9% of Control IQ users

Another session that caught my eye was by Tandem’s Laurel Messer who asked, “What happens if people don’t bolus for a week?” I confess that when I heard that T Connect data from 272 000 Control IQ users showed that over 9% of people had over one week in a three year period during which they didn’t bolus at all, I inwardly cheered! Good on them for living the fully closed loop dream. However, there are many reasons why people might not bolus for a week. Maybe they were trying a low carb diet and wanted to see how the system worked for that without bolusing, maybe they were injecting manually for meals, or using Afrezza, rather than using the pump, or not wanting to bolus in front of people or stop what they were doing to bolus, or there could be unfortunate factors eg insulin rationing due to cost of insulin, restrictive dieting, or not realising they were supposed to bolus for meals with Control IQ.

Interestingly, the outcomes for this group of users showed that their time in range was higher during the week when they didn’t bolus than when they did bolus.

The median number of consecutive days during which this “fully closed loop” group of users did not bolus during a three year period was 11. And for these users, the average number of non-consecutive days over a three year period during which they didn’t bolus was 22-66 days.

Laurel Messer concluded her presentation saying they really didn’t know why people had these periods of fully closed loop use with Control IQ, but suggested the following might be involved:

- It’s difficult to persistently maintain self-management behaviours

- Users might be satisfied with the glycemic outcomes they get using fully closed loop

- A change in circumstance (change in diet, activity, illness, medication, use of GLP-1.)

*Also worth noting that ‘fully closed loop’ for this Tandem study was defined by 0 carb boluses and less than or equal to 1 manual bolus per day.

Tandem was just one of the many insulin pump companies at ATTD 2024 presenting data about fully closed loop and the need to create advanced algorithms to make fully closed loop even more effective. The device data is fascinating as it gives hints as to what research is needed in this area to understand what is really going on for users.

Designing systems for people with disabilities

At the #Dedoc symposium, ‘What we wish you knew – and why’ run by people living with diabetes, Nur Akca spoke about the need for companies to keep people with disabilities in mind when designing pumps and diabetes device systems. She was diagnosed with congenital cataracts at three months of age, and now lives with low vision. She asked companies to include a high contrast option and easy to access brightness adjustment tools for screen displays and to provide more opportunities for people to actually see, hold and operate insulin pumps, before making a decision on what system to commit to, saying that she had repeatedly been told “just to try out the simulator”, which was not useful to her especially given her low vision.

I often wonder if designers realise that a significant proportion of their users are over 45 and need reading glasses to see the small font in their diabetes system displays. And I’m pleased to see some pump companies are continuing to include a button for bolusing with their pumps as this kind of tactile option can be very handy for people on the go, regardless of age or disability.

Omnipod OP5 data shows people in different age groups choose different BG targets

May Ng from the UK, presented some fascinating data from a study by Greg Forlenza et al (published online one week after the conference, see reference at end of blog post) on the blood glucose targets that are chosen by people in different age groups.She mentioned that many parents of very young children (age 0-5) choose a higher BG target over a 6.1mmol/L target due to concerns about children experiencing hypoglycaemia at night.

May Ng and Trang Ly (Insulet) stressed the importance for users of being able to personalise their own BG targets, and Trang Ly said hypoglycaemia minimisation remains a major goal for Insulet as they test algorithms for fully closed loop.

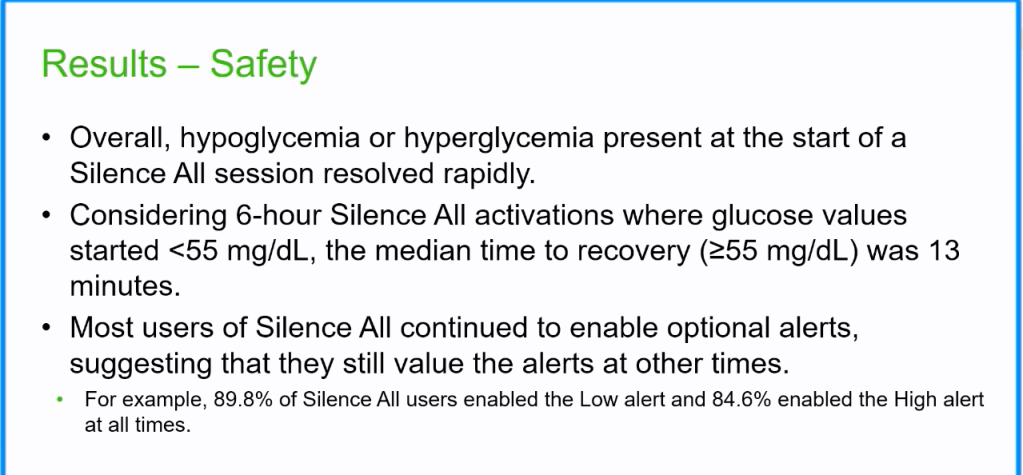

‘SILENCE ALL’ No alerts for six hours, Dexcom G7

Being able to customise and silence cgm alarms is critical to my quality of life and ability to work, so I was also drawn to Dexcom’s presentation on how people are using the new “Silence All” feature of the G7.

The ‘Silence All’ feature allows users to totally silence their cgms for six hours. It also stops alerts that usually vibrate from vibrating for six hours. During this time, alerts still appear on the user’s screen.

Anonymised device data was analysed from 106 526 Dexcom G7 users, predominantly from the US (38% T2D, 28% T1D, 1% pre-diabetes, 0.0% gestational, 0.5% LADA, 31% unknown.) As for the results, the slides below speak for themselves.

This blog post is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what was presented at ATTD2024 and has mainly focused on a fraction of the data related to diabetes device use.

I was extremely grateful to also have the opportunity to attend sessions on developments in diabetes prevention, islet cell replacement, AI, advanced insulins, drugs, closed loop algorithms, the health economic aspects of these possibilities, and more. This conference was an over 1000 abstract cornucopia of what’s just happened, what’s in the pipeline and what issues still need to be addressed in the world of diabetes.

In the words of my friend, open source developer Tim Gunn, who attended more of the ‘in the pipeline’ tech sessions than I did, “some of these pieces of tech won’t see the light of day, but it’s reassuring that companies and individuals are plugging away to help keep advancing the care of diabetes.”

References

Josie Clarkson’s “We Will Stop Type 1 Diabetes” (Josie is the research communications lead for JDRFUK)

Leon, Practical Diabetic Highlights from ATTD 2024

Martin Scivier’s Tech Fair coverage from ATTD 2024

Dana Lewis’s excellent guide to dosing for meals using automated insulin delivery systems

Link to the research mentioned in Bill Polonsky’s presentation on the benefits of CGM use in T2D. The Potential Impact of CGM Use on Diabetes-Related Attitudes and Behaviors in Adults with T2D: A Qualitative Investigation of the Patient Experience

Links to research mentioned by Mike Riddell on T2D intermittent fasting, exercise and beta call function. Efficacy and Safety of Intermittent Fasting in People With Insulin-Treated Type 2 Diabetes (INTERFAST-2)—A Randomized Controlled Trial

Link to the research May Ng mentioned by Greg Forlenza et al (2024) showing BG target set varied by age group for the Omnipod 5. Real-World Evidence of Omnipod® 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System Use in 69,902 People with Type 1 Diabetes