A few months ago I met a 96 year-old man in my dentist’s waiting room. I told him I had an artificial pancreas.

I was ecstatic – showing my OpenAPS rig to complete strangers at the time, expecting them to be as interested and thrilled as I was about this monumental development. Most people looked a bit puzzled. Some remembered hearing or reading something about type 1 diabetes and proceeded to ask me if I was one of those people who had to give myself injections.

The man in the waiting room was quiet for a long time. He shook his head. He was quiet again. I thought I’d been too forward and maybe what I’d said was unfathomable to him.

Then he told me that a boy in the year behind him at primary school, when he was in year six, had died of diabetes, and a boy the year ahead of him with diabetes had not reached his twenties.

I was shocked. Since my own diagnosis in 1980, I’d assumed the discovery of insulin in 1921 meant that the era of children regularly dying from diabetes was a bygone era, a chapter in ancient medical text books (and developing countries, and America if you don’t have health insurance, but that’s another story).

I did the maths. The man in the dentist’s waiting room was born in 1922, the year that insulin became available for treating type 1 diabetes. He would have been in year six in 1932. So the first boy had died around 10 years after the discovery of insulin and the boy who didn’t make it into his twenties maybe started using insulin in the early 1930s.

It was humbling and profound to realise that in the span of one living human’s life, the world had changed from one in which type 1 diabetes equalled death to one where hybrid closed looping technology had been developed, and a healthy, long life could be the norm.

It also made me wonder what it was like to live with type 1 diabetes in Australia during those early years of insulin. Why did people do so poorly?

I stumbled upon Vicky Bowden’s story of John Cook in Mackay’s Daily Mercury, 10 May 2018. It provided a lot of the answers:

“Even with the advent of insulin the treatment was fraught with danger, as the potency of the drug was variable, leading to complications in many patients. It was also expensive and availability was sometimes patchy.”

According to Lance Macaulay’s article in Australian Biochemist (2002) the high cost of insulin, and issues with availability, led many families to rely on dietary restriction to minimise the amount of insulin required, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Lance Macaulay describes his own father, Russ, who was diagnosed in 1930 at age three, remaining thin and physically wasted on the restrictive diet of the times, until he visited a new clinic at age 14, was placed on a regular diet and thrived.

John Cook developed diabetes in 1925 at age 13, two years after CSL began producing insulin in Australia.

John followed a strictly controlled and documented diet and measured the sugar in his urine four times a day. He also weighed himself on a daily basis to gauge how well the insulin treatment was working.

When he was fourteen years old, he developed “pain in my side” and despite the local doctor assuring him it was nothing to worry about, he was later taken to hospital by ambulance and remained there for two and a half months.

By the end of his hospital stay, fourteen-year-old John had put on “1/4 pound”. His diaries show that he struggled in hospital with the slow passing of time, and found the days without visitors hard to bear. His father’s diaries note that he was becoming depressed. They brought him home.

Vicky Bowden, who chairs Friends of Greenmount Homestead, says that over the years “John became desperate to find another way of treating his illness”.

His parents embraced natural health practices and became interested in Christian Science, a movement that was growing in popularity at the time. Christian Science founder, Mary Baker Eddy argued in her 1875 book, Science and Health, that “sickness is an allusion that can be corrected by prayer alone.”

John persuaded his mother to take him to see Christian Science practitioners in Brisbane in March 1929. His parents would only agree to the trip if he promised to continue taking his insulin. He agreed, but he wanted to stop.

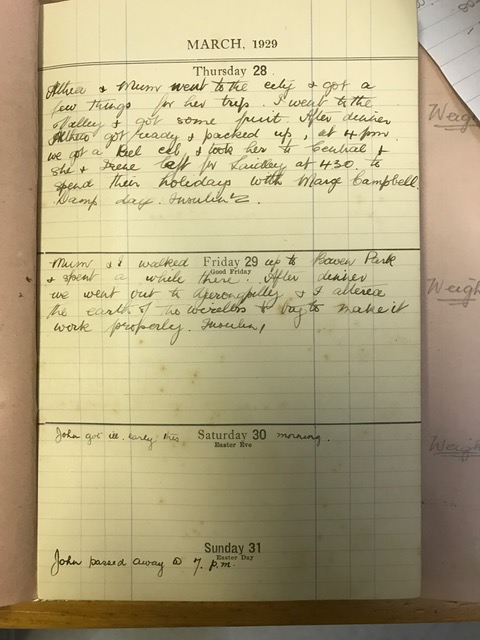

John Cook had kept a detailed diary from the age of eleven. The entry from 7 March, 1929, indicates that he was told he could not be healed unless he gave up his insulin. According to Vicky Bowden, his diaries note that his insulin doses were gradually reduced over the following weeks.

The last word John wrote in his diary is “insulin”, on 29 March, 1929. The final words in his diary are his mother’s.

John Cook died at 7pm on 31 March 1929 at seventeen years of age, after becoming ill early on the morning of 30 March.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

What captured my attention most of all in Vicky Bowden’s Daily Mercury article is the following description of John:

“John spent a lot of time designing new machines and redesigning old ones. His drawing book shows all manner of engines and devices all neatly sketched and labelled in his hand.”

And from one of the eulogies written about him:

“John was a bright, cheery lad and was exceptionally clever, particularly in mechanical lines. Although only very young, he could assemble the parts of motor cars with the greatest ease, and wireless work of the most difficult nature was only a mere detail to him.”

“He could discuss most intricate questions and work with the most learned, and possessed the most genial character of profound meekness.”

John just needed access to the internet, and to be born sixty years later.

I hope one day to visit Greenmount Homestead and look at John’s diagrams. I’m sure you all know what I am looking for…

Sincere thanks to Vicky Bowden, chair of the Friends of Greenmount Homestead, for providing digital photographs and information to me about the life of John Cook.

I started writing this with an upbeat ending in mind. The truth is, it’s a very sad story. It reminds me of the great luck we have to be alive at this point in history. It reminds me to be grateful, every day. And it reminds me of how much is left to do in countries and amongst people who are not as fortunate as we are.

This Christmas, I’m following in the footsteps of the Grumpy Pumper and his advent of Insulin idea…